There's been much talk on news and film websites this week about the passing on the same day of both Ingmar Bergman and Michelangelo Antonioni, two directors whose names are synonymous with the potential of film as an artform. And, for cinephiles, it certainly feels like the end of an era, much in the same way I keenly felt the passing of the classic Hollywood era back when both Jimmy Stewart and Robert Mitchum died within a day of each other back in 1997.

Both directors' films had a profound impact on my development as a film viewer. Now, don't get me wrong--I love to see movies where shit blows up. But there are some days when I need to see John McClane surfing on the back of a fighter jet, and there are other days when I need to see a film that readjusts my understanding and expectations of what cinema can accomplish as an artform. (But now that I think about it, shit does blow up in Antonioni's film Zabriskie Point. It does not, however, in Blow-Up: a movie that, despite its title, is completely explosion-free.)

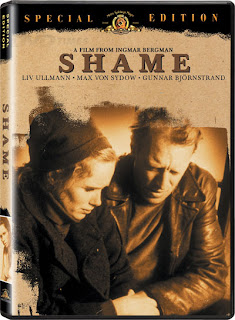

When I was an undergraduate, the university I attended had an annual international film festival, and during my junior year, I volunteered to be on the committee that selected the films. One of the goals of the festival was to give people an opportunity to see some of the classics of world cinema that they might not get to see otherwise. To this end, the festival would feature, every year, one Kurosawa movie, one Bergman, one French New Wave, and so on. For this particular series, I volunteered to pick the Bergman film, and I chose his 1968 film Shame. The film professor who ran the series seemed happy with the choice, seeing that I could go a little deep into Bergman's oeuvre and choose something other than the typical choices, like The Seventh Seal, Wild Strawberries, and Persona. Shame stars Bergman staples Max Von Sydow and Liv Ullmann as married musicians trying to survive in a near-future world ravaged by civil war. This is a bleak movie, and the black and white cinematography utilizes over-exposure to create a high-contrast effect with little gray. Just how bleak is this movie? I heard that when Gregor Samsa watched this movie, he said to his family, "You know what? My life's not so bad." The film ends with one of the most depressing and powerful scenes in all of cinema: Von Sydow and Ullmann attempt to escape their war-torn country by boat, but as they move along the river, they find it increasingly clogged with corpses.

Shame stars Bergman staples Max Von Sydow and Liv Ullmann as married musicians trying to survive in a near-future world ravaged by civil war. This is a bleak movie, and the black and white cinematography utilizes over-exposure to create a high-contrast effect with little gray. Just how bleak is this movie? I heard that when Gregor Samsa watched this movie, he said to his family, "You know what? My life's not so bad." The film ends with one of the most depressing and powerful scenes in all of cinema: Von Sydow and Ullmann attempt to escape their war-torn country by boat, but as they move along the river, they find it increasingly clogged with corpses.

Needless to say, the screening did not go well, with a very strong negative reaction from the audience. The next day, I was talking to a Philosophy professor about it, and he responded, "So, you're the one who picked that film. I could have told you not to do that. At the very least, you should have shown some Three Stooges shorts afterwards." Last summer, I spent a day watching the 5-hour version of Bergman's Scenes from a Marriage, available from Criterion, which originally aired on Swedish television and was later re-edited into a feature film. It's an incredible exploration into one couple's emotional failures, and most of the film only features the two main characters--played by Liv Ullmann and Erland Josephson--in conversation. Bergman uses long takes and a static camera to present an unflinching view of this couple's life, and it forces you to watch their emotional decline into violence. Like many of Bergman's films, it is not easy to watch, but it is ultimately rewarding in profound and complex ways.

Last summer, I spent a day watching the 5-hour version of Bergman's Scenes from a Marriage, available from Criterion, which originally aired on Swedish television and was later re-edited into a feature film. It's an incredible exploration into one couple's emotional failures, and most of the film only features the two main characters--played by Liv Ullmann and Erland Josephson--in conversation. Bergman uses long takes and a static camera to present an unflinching view of this couple's life, and it forces you to watch their emotional decline into violence. Like many of Bergman's films, it is not easy to watch, but it is ultimately rewarding in profound and complex ways.

I frequently teach Intro to Film classes, and though I've never taught a Bergman film, I have taught Michelangelo Antonioni's Blow-Up (1966). The film tends not to go over very well with students, mainly because it so challenges their expectations and basic needs for sympathetic characters and narrative closure that their immediate critical reaction is that it's bad rather than just different or even liberating. (Or just plain cool, if only for the Yardbirds scene, with Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page on-stage together.) Several students, however, have commented to me years after taking the class that Blow-Up has stayed with them, and they appreciate it better over time.

I would rank Blow-Up among my top ten favorite movies of all time (if I had to put together such a list--though there may be about 40 movies that I claim are in my top ten right now), and I would also include Antonioni's L'Avventura (1960) on that list as well. Very few movies give me as much pure pleasure as L'Avventura, despite the fact that I find the main characters completely unsympathetic, and, as in Blow-Up, the plot does not resolve itself in any conventional way. This may also be one of the most perfect and beautifully shot movies in history, even though Antonioni often eschews some basic conventions of narrative continuity (for example, in some shots, he will have a character enter from the right side of the screen, but then cut to a shot with the same character on the left side. Such breaks in continuity may not be noticeable or even seem important, but they can have a subconsciously jarring effect, as we are trained by basic film grammar to expect a character to stay on the same side of the screen throughout a scene.). And Monica Vitti is just freaking hot, so the movie has that going for it, as well.

I think the presence of Blow-Up and L'Avventura among my favorites says more about my tastes in film than any other two movies. I love the way these movies challenge my expectations, and every time I watch them, I feel reinvigorated in my enthusiasm for the potential of film in general (though when I show Blow-Up to students, I have a twinge of embarrassment during Thomas's three-way scene with the two teenage girls).

Through these two directors, I not only learned about cinema as an artform, rather than as a purely escapist entertainment medium, but I also had my consciousness expanded to include other types of stories that I had never experienced before and a greater understanding of humanity in general.

You love L'Avventura and Blow-Up, but no mention of L'Eclisse? It always seemed to me that L'Avventura was a warm up for L'Eclisse, which is the real masterpiece of Antonionni's early trilogy.

ReplyDeleteThanks for mentioning Shame, a great film, and one of Bergman's most overlooked. I think I read somewhere that it was one of his personal favorites as well. Not surprised the college audience of today couldn't stomach it though. I once showed Dovzhenko's Earth to a class. From their reaction, you would have thought I had force-fed them lima beans.

I think you're right about L'Eclisse, though I don't have as much of a personal connection to it as I do to L'Avventura. I was focusing on the movies by these two directors that I experienced during my early development as a film viewer. I came to L'Eclisse very late--I think upon the release of the Criterion edition--and I haven't watched it the dozens of times that I've watched the other two movies.

ReplyDeleteI may have read something similar about Bergman's feelings regarding Shame, which probably led me to choose the movie for the film festival.

And I can imagine Dovzhenenko's Earth being tough for students.

i am a novice when it comes to movies of these great movie-makers but have been reading about them for a long time now but I thought you summed up your thoughts so beautifully - esp. the last sentence 'Through these two directors, I not only learned about cinema as an artform, rather than as a purely escapist entertainment medium, but I also had my consciousness expanded to include other types of stories that I had never experienced before and a greater understanding of humanity in general.' - wonderful

ReplyDelete